Well, we’re about halfway through summer now, but that doesn’t mean we don’t have time for more summer reading!

The HWA’s summer reading recommendation program, Summer Scares, is ongoing. Earlier this summer, I went over committee member Kiera Parrot’s middle grade suggestions, but she isn’t the only one on the committee to have made additional recommendations. Grady Hendrix, author of a number of excellent books including the reference book Paperbacks from Hell, which covers paperback novels from the 1970s and 1980s, recommended a few older titles.

Wait Till Helen Comes by Mary Downing Hahn

HarperCollins, 1987

ISBN-13: 978-0380704422

Available: Library binding, paperback, Kindle edition, audiobook, MP3 CD

You might remember that Kiera Parrot recommended a recent book by Mary Downing Hahn, The Girl in the Locked Room, in our previous booklist of middle-grade recommendations for Summer Scares. Mary Downing Hahn has been writing since the 1970s, and Wait Till Helen Comes is one of her earlier books. Published in 1986, it has received multiple reader’s choice awards and was made into a movie. A reread of Wait Till Helen Comes shows that it is still seriously creepy. The story starts with narrator Molly’s mother remarrying to a man named Dave, whose daughter Heather is troubled and possessive of her father after her mother died in a fire. The new family moves to a converted church in the middle of nowhere, under Molly’s protest. Molly’s mother tells Molly that as the older child, it is her responsibility to take care of and get along with Heather, who is openly hostile to both of them, to Dave’s obliviousness.

Together, Molly and Heather discover a graveyard on the property, with a stone that has the initials H.E.H, the same as Heather’s. Heather becomes obsessed with discovering who it is, and Molly witnesses her having a conversation with a ghost girl called Helen. When Molly brings it up with their parents, Heather denies it and Dave and Molly’s mother dismiss it as superstition and imagination. When Heather and Molly are alone, though, Heather threatens Molly, and one day when the family is out of the house, they return to discover that Molly’s and her mother’s things have been destroyed. Once again, their parents accuse Molly of making things up to make things more difficult for Heather.

After learning that Helen drowned after escaping a fire where her parents died, and that a number of girls have drowned since then in a nearby pond, Molly decides she must break Helen’s hold over Heather before someone dies. The climactic scene between Helen, Heather, and Molly, will leave your heart pounding fast. While far from perfect, the story is atmospheric, suspenseful, and compelling enough to overlook any flaws, especially if you’re 9 years old. The book does deal with death, grief, and suicide, so some people have raised objections to it in the past, but in the fantasy context I don’t think it’s likely to lead to more.

The House With a Clock in Its Walls (Lewis Barnavelt, #1) by John Bellairs, illustrated by Edward Gorey

Puffin, 2004 (reprint edition)

ISBN-13: 978-0451481283

Available: Library binding, paperback, Kindle edition, audiobook, audio CD

First published in 1973, this is another classic, not just in middle-grade horror (or Gothic mystery, if you’d rather), but in children’s literature. It is 1948, and 10 year old Lewis Barnavelt’s parents have died, so he is sent to live with his eccentric Uncle Jonathan. Jonathan and his neighbor, Mrs. Zimmerman, are magicians, and Jonathan’s house previously belonged to Isaac Izzard, a warlock, or black magician, who has a clock with an unknown purpose ticking away in the walls. As a result, Jonathan has filled the house with clocks to cover over the sound. It’s enough to make a magician uneasy enough to stop the clocks in the middle of the night, and Lewis is just a kid.

If Lewis only had to interact with Uncle Jonathan and Mrs. Zimmerman, the book would be filled with oddities, quirky moments, minor wonders, and an illustration of what the friendship of long-term, close, and very different friends looks and feels like. And it does have those things. But when school starts, Lewis has to find a place among his peers, and as he’s not athletic, he’s soon left in the dust. One of the popular, athletic boys breaks a leg and starts spending time helping Lewis with athletic skills, and in hopes of continuing the friendship Lewis boasts of his uncle’s magical powers, first claiming that Jonathan can block the moon and then suggesting that the two boys use his spellbook to raise the dead. Sneaking out in the middle of the night, Lewis and his friend recite the spell in front of an unknown tomb and really do manage to raise the dead. Unsettled by his experiences with magic, Lewis’ friend abandons him, leaving him on his own, to deal with the person he has raised from what turns out to be Isaac Izzard’s crypt– a person who wants to find the clock in the walls of his uncle’s house.

This is a great book for so many reasons. Lewis himself is kind of an oddball kid, reading historical lectures late into the night and reciting Catholic prayers when he’s anxious. Awkward around his peers, he is interested in puzzles and spells, and brave enough to confront his fears. While he doesn’t want to admit his mistakes, in the end he takes responsibility for his actions and resolves what has become a terrifying situation in a creative way. In a strange environment, he adapts to becoming part of the rather odd friendship/family of Mrs. Zimmerman and Uncle Jonathan, who may bicker with each other but are loyal and stand up for each other when it counts. You might have to get today’s impatient kids to stick with the book through the first few pages of Lewis’ train ride and Latin recitations, but upon meeting Uncle Jonathan, they’ll want to know more. Even though the story has a slow build, it is interesting along the way, and once it speeds up, readers won’t want to stop.

I can’t not mention that Edward Gorey illustrated this book. His illustrations are what set the mood for the story, and the book wouldn’t be the same without them.

Gegege no Kitaro (The Birth of Kitaro) by Shigeru Mizuki

Drawn & Quarterly, 2016

ISBN-13: 978-1770462281

Available: Paperback

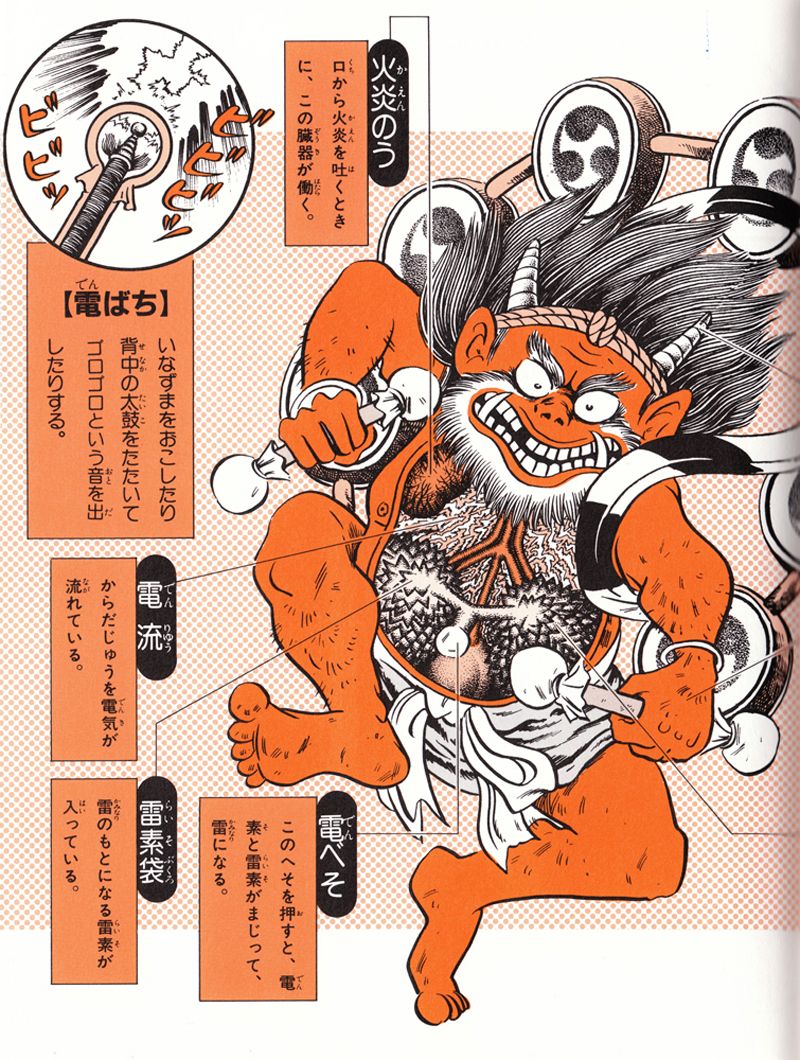

Kitaro is a manga series by artist Shigeru Mizuki that dates back to the 1960s, described by David Merrill as ” the seminal yokai-busting horror-fantasy-folkore-adventure-comedy manga”. The titular character, Kitaro, is a young boy with one eye who serves as a diplomat between humans and yokai (Japanese folk monsters). Originally a more adult title called Graveyard Kitaro, the series really took off when it was retooled as GeGeGe no Kitaro to be more of a funny-scary series for elementary-aged kids, and was even spun off into several different television shows. While Kitaro is somewhat of a pop culture phenomenon in Japan, it hasn’t been well-known in the United States. The publisher Drawn & Quarterly has been releasing English-language volumes of Kitaro over the past several years. The first is out of print, but The Birth of Kitaro shares Kitaro’s origin story, so it might be a good place to start. I haven’t had the opportunity to examine these myself, but I saw and (briefly) blogged about Mizuki’s yokai art last year, and it is amazing. For some adult manga lovers, Kitaro may have more nostalgia or historic value than anything else, but it looks to be a great choice for middle-grade readers who love monsters.

Wait Till Helen Comes and The House With a Clock in Its Walls are pretty well known in the world of children’s literature, but Kitaro won’t be familiar to a lot of librarians or middle-grade readers. Summer Scares gives you the opportunity not only to introduce some old, familiar favorites, but to bring to light some lesser-known titles that deserve more of a spotlight and increase the breadth of kids’ exposure to manga as well as to creatures and stories from another country and culture. Enjoy!

Follow Us!