( Bookshop.org | Amazon.com )

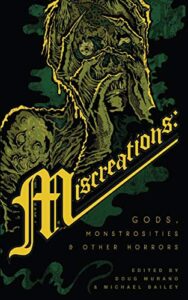

Miscreations: Gods, Monstrosities, and Other Horrors edited by Doug Murano and Michael Bailey

Written Backwards, 2020

ISBN-13 : 978-1732724464

Available: Hardcover, paperback, Kindle edition

In the foreword to Miscreations, Alma Katsu writes that “we’re told from childhood that monsters exist… we don’t need anyone to tell us they’re real”. Collected within the pages are 23 tales of monsters of all kinds, from the traditional to the unconventional, from the literary to the personal. Interspersed is artwork from HagCult, who also did the cover art for the book.

Josh Malerman gives us a werewolf tale in “One Last Transformation” with an engaging, murderous narrator addicted to the change, and a number of writers approach the Frankenstein story in different ways. My favorites of these tales were Stephanie M. Wytovich’s poem “A Benediction of Corpses” in which the Creature addresses his creator directly, and “Frankenstein’s Daughter”, by Theodora Goss, with its surprising and satisfying ending. Christina Sng takes an unconventional approach to an evil Russian water spirit in “Vodoyanoy”.

More personal monsters also appeared. Michael Wehunt’s “A Heart Arrhythmia Creeping Into A Dark Room” was an effective and creepy tale about the anxiety and dread that accompany someone living in the shadow of a potential heart attack. The story was flawed by the author’s insertion of a fictionalized monster and victim in a story that was far too realistic. Victor Lavalle’s “Spectral Evidence” touched on the way grief lives on, and Scott Edelman’s “Only Bruises Are Permanent” tells the story of a woman who has the bruises left from an incident of domestic violence tattooed on her body.

Monstrous mothers also appear, in Joanna Parypinski’s brutal “Matryoshka”, in which a family tradition of giving each mother and daughter a matryoshka doll goes dramatically wrong, and Mercedes M. Yardley’s ironic “The Making of Asylum Ophelia”, in which a mother raises her daughter to resemble Hamlet’s Ophelia with plans to also replicate her fate.

Other strong stories I especially enjoyed include Nadia Bulkin’s “Operations Other Than War”, Usman T. Malik’s “Resurrection Points”, Lisa Morton’s “Imperfect Clay”, and the disturbing “My Knowing Glance” by Lucy A. Snyder, which went in a much different direction than I expected it to.

Miscreations is overall a strong collection. The authors have come up with imaginative creatures using a variety of creative approaches, and readers will find sitting down with it well worth their time. Highly recommended.

Contains: murder, torture, violence, gore, body horror

Reviewed by Kirsten Kowalewski

Editor’s note: Miscreations: Gods, Monsters, and Other Horrors is a nominee on the final ballot for the 2020 Bram Stoker Award for Superior Achievement in an Anthology.

Follow Us!