I attended G-Fest this past weekend with my son, who is a huge Godzilla and kaiju fan (for those of you who don’t know what kaiju are, they are giant Japanese movie monsters, most of which have been created since the original Godzilla movie premiered in 1954. If you are a Gen Xer, you probably saw them on Saturday night and Sunday afternoon television).

While I’m not a huge Godzilla fan myself, I have lived with two of them, and it’s an education. But their enthusiasm in collecting action figures and watching the movies is nothing compared to the contagious love of the genre and almost everything about it that I experienced at G-Fest. You have to dig deep to find the kind of information some of the people running the sessions shared.

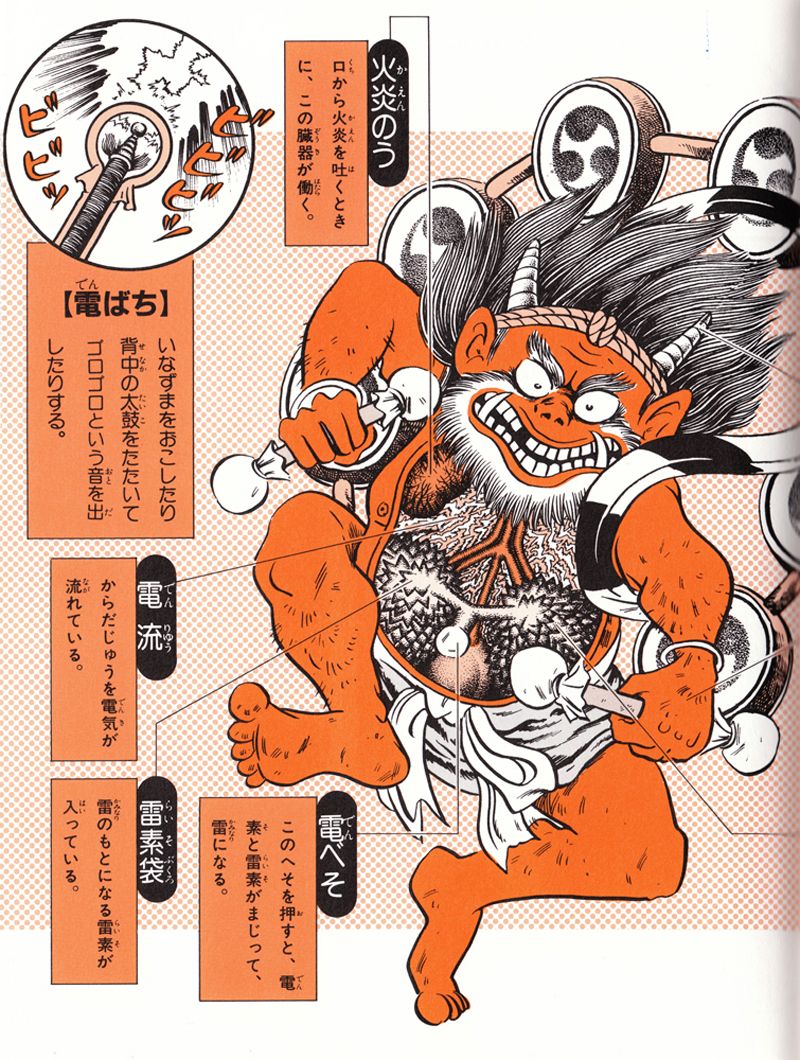

The last session I attended was about art depicting Japanese monsters. One of the artists responsible for documenting Japanese monsters put incredible effort and artistry into depicting Japanese folk monsters, called yokai, particularly in the manga series Ge Ge No Kitaro. Eisner Award winner Shigeru Mizuki started out drawing pictures for Japanese story theaters called kamishibai, before the popularity of manga, studied and drew yokai from both the outside and inside (unfortunately, he died in 2015).

Drawing near the same time was another artist, Shoji Ohtomo. What Mizuki did for yokai, Ohtomo did for kaiju. His drawings show how interested he was in the details of what made kaiju work, and many people called him “Dr. Kaiju”. Unfortunately, while you can find a reasonable amount of information on Shigeru Mizuki, it’s not as easy to find the same

Cross-section of King Ghidorah (left), photo of Shoji Ohtomo (right).

about Shoji Ohtomo. Here’s a short piece I found over at Monster Brains that includes several of his anatomical drawings. And a few of my very blurry photos from the session, run by Stan Hyde.

Anatomical drawings of Gappa (left) and Gamera (right) by Shoji Ohtomo.

You have to really care about monsters to want to imagine what they would be like inside if they weren’t fictional characters represented by an actor in a rubber suit.

Shoji Ohtomo is also credited by some with the original design of Ultraman, an alien kaiju fighter. Ohtomo’s original drawing appears on the right, with more finished designs on the left. Before I became a children’s librarian, I wanted to be an archivist and manuscripts librarian, and getting to see the details that go into the process of creation, whether it is drafts of a poem by Sylvia Plath or the development of a character like Ultraman is why I wanted to do that.

Original drawing and cross-sections for Ultraman, by Shoji Ohtomo

It’s easy to write off some of these films as cheesy B-movies. As a genre, they do indeed have their cheesy, goofy moments. But there are many talented artists in a variety of mediums who have contributed to the development of kaiju eiga films and there is a lot more going on than there seems to be on the surface. Because so much of what makes these movies work occurred (and occurs) in Japan, and (at least given my experience at this convention) many of the makers and actors aren’t known outside Japan(three of the special guests needed a translator), most people don’t get to appreciate that.

What does any of this have to do with the horror genre? Well, if it had nothing to do with it, this would still be really cool to see. But besides stories about giant monsters being part of the stock in trade, many creators in the horror genre expend the same kind of attention to detail in crafting their art, and in the past have found their work similarly dismissed. I encourage you to explore the different ways monsters and horror are experienced around the world, so you can see that love of the genre expressed in the many different ways people perceive it. Look further, and find even more to love.

Follow Us!