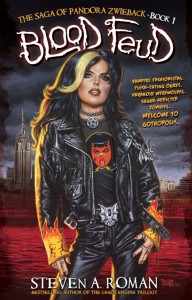

Steven A. Roman is the bestselling author of X-Men: The Chaos Engine Trilogy and Final Destination: Dead Man’s Hand. His latest work is the dark-urban-fantasy adventure Blood Feud: The Saga of Pandora Zwieback, Book 1.

Blood Feud is about Pandora, a young woman who discovers monsters are real in NYC and only she can see them, which gets her sucked right into a vampire war. So why vampires? Why do you think they’re so popular?

Why vampires? Because even when I originally pitched this series to R. L. Stine’s company, Parachute Press, in 1998, I knew that vampires have always sold books—and that’s even truer now! You can’t walk through a Young Adult section of a bookstore without tripping over the stacks and stacks of vampire novels being published these days.

As for why they’re so popular… well, zombies might be “the new black,” but I don’t know many people who’d want to have sex with moldy, flesh-eating corpses (besides, that’s a whole ’nother genre!). Werewolves are more interested in eating their victims than wanting to mate with them. And both zombies and werewolves are generally lacking in character—they’re single-minded killing machines with no personality. They’re not the cuddling type.

Vampires, though, are sooooo dreamy…

Dracula, Nosferatu, Lestat de Lioncourt, Edward Cullen…what’s your favorite ″kind″ of vampire and why?

My favorite kind of vampire would be the comic book character Vampirella—but that probably has more to do with her battling evil in just a one-piece swimsuit and go-go boots than because she drinks blood.

My favorite kind of vampire would be the comic book character Vampirella—but that probably has more to do with her battling evil in just a one-piece swimsuit and go-go boots than because she drinks blood.

In terms of something more literary, I really enjoyed the “Sonja Blue” novels by Nancy A. Collins. Sunglasses After Dark is as far from sparkly emo vampires as you can get, and shows there’s nothing even remotely romantic about getting your throat torn out by some bloodthirsty ghoul—it’s nasty and brutal. On the plus side, though, being a vampire means Sonja is a major ass-kicker.

The vampires in Blood Feud are closer to that version of bloodsucker, mixed with the leather-wearing vampire warriors of the Underworld movies and the Elegant & Gothic Lolita fashion style of Japan. And while Blood Feud introduces only three clans (and name-checks a few others), its sequel, Blood Reign, will include other vampire houses from around the world.

Besides, any creature of the night that sparkles in sunlight isn’t a vampire—it’s somebody who got covered in glitter at an all-night rave and stumbled outside in the morning!

What books, movies and comics were most meaningful to you as a teen?

Well, Stan Lee was my first writing influence, but what really caught my attention were the horror comics published in the 1970s: Vampirella, Ghost Rider, Werewolf by Night, Tomb of Dracula, Son of Satan, Frankenstein’s Monster, Man-Thing—it was a great time to be a horror comics fan! It’s those comics that still have an influence on my writing for the Pandora Zwieback novel series, and for a separate graphic novel series that stars a “soul-stealing succubus” named Lorelei.

’Salem’s Lot was the first Stephen King novel I read, and it scared the hell out of me! I used to read it once a year through high school.

Probably the oddest influence that remains from my teen years, considering I write dark fantasy and horror, is the British science fiction series Doctor Who. If you take the setup I give folks of the Pan Zwieback series (“16-year-old Goth teams up with a 400-year-old, shape-shifting monster hunter”) and turn it around (“a being hundreds of years old, who can change their appearance, fights monsters with the aid of a female companion”) you’ve got the most basic description of the Doctor and his multiple sidekicks.

Which ones do you think are essential reading for today’s teens?

I don’t read a great deal of Young Adult novels—although, for example, I do have copies of Markus Zusak’s The Book Thief, Joyce Carol Oates’s Zombie, and J. M. DeMatteis’s Imaginalis in my to-read pile—so I don’t know which books might be “essential.” I tend to recommend books like Ray Bradbury’s Something Wicked This Way Comes and Dandelion Wine. I did, however, enjoy Lord Loss, the first book in Darren Shan’s Demonata series. It’s sort of Clive Barker Lite!

On the other hand, I don’t think they’ve ever been marketed as YA novels (they’re certainly not middle grade!), but three books that I highly recommend are:

• The Girl Who Loved Tom Gordon, by Stephen King: Nine-year-old city girl Trisha McFarland wanders off a forest path after arguing with her mom and gets completely lost—then things get really bad. Something stalks her through the woods, and it’s only her love for real-life (now former) Boston Red Sox relief pitcher Tom “Flash” Gordon that keeps Trisha going through all her freaky adventures.

BTW, it also made for an absolutely insane adaptation—as a children’s pop-up book! I don’t know what the publisher was thinking; it’s a real nightmare-inducing storybook for little kids. Maybe that’s why I like it so much…

* Cycle of the Werewolf, also by Stephen King: There’s a werewolf on the loose in Tarker Mills, Maine, and the only person who can stop it is 11-year-old Marty Coslaw, who’s a paraplegic. But even though he’s confined to a wheelchair, Marty’s smart enough, and brave enough, to discover the werewolf’s identity. Now if he can just kill it before it kills him…

• True Grit, by Charles Portis: Yes, the very novel that served as the basis for two movie adaptations. Although the films were more focused on John Wayne’s and Jeff Bridges’s respective portrayals of U.S. marshal “Rooster” Cogburn, the novel really makes it clear that this is the story of Mattie Ross, a 14-year-old girl searching for her father’s killer. Mattie’s a strong female character who knows what she wants, with a sense of humor so dry it makes her a little too straitlaced at times, but it’s a fast-paced, enjoyable adventure.

How is writing an original novel different than writing for say, Marvel or Final Destination, like you have?

The main difference is that, for any novel based on licensed material, there’s an approvals process you have to go through. Basically, you’re playing with other people’s toys, and they’re very exact in how they want them returned.

At least the ones who know what they’re doing are exact in how they want them returned…

With X-Men: The Chaos Engine Trilogy, Marvel Comics’ licensing division had approval over the plots and manuscripts. The first novel, X-Men/Doctor Doom, was a breeze, and went on to sell a ton of copies when it hit bookstores in early 2000, thanks in no small part to the book coming out in time for the release of the first X-Men movie.

Unfortunately, the second and third books became increasingly problematic because Marvel fired the people who’d approved my plots and first manuscript and replaced them with “editors” who had their own agendas—for instance: one was the publisher’s personal assistant, who had no editorial training whatsoever but a head full of political correctness. Handing me notes that I should write “up” to the level of a comic book, or that describing one character’s features as “exotic” was forbidden because “it’s a racially-charged term for women of color” (WTH?!) isn’t editorial guidance for improving a story—it’s an expression of personal likes and dislikes, and has no business in the creative process.

Eventually, Marvel wised up and assigned someone who did have editorial experience. Unfortunately (again), that guy had an ax of his own to grind, apparently because he’d never been asked to write an X-Men novel. So why should he make things easy for me, right?

You know the old saying about dogs peeing on things to mark their territory? It was just like that.

Two more editors and two years later, the final books in the trilogy—X-Men/Magneto and X-Men/Red Skull—were allowed to come out. They also sold well, but without the higher numbers they might have had if they’d been published closer to Book 1’s release—and if Marvel hadn’t delayed them by hiring so many cooks to spoil the broth.

At the other end of the spectrum, Final Destination: Dead Man’s Hand went from inception to printed book in a fairly painless process, although a lot of that had to do with the fact that the editor for the series asked me to come up with a plot over a weekend and write the book in a three-month period, to fill a gap when another author dropped out. There’d be no time for a second draft!

A big advantage was that the Final Destination franchise doesn’t have a set cast of characters—every movie and story introduces a whole new group of victims for Death to kill—so not a whole lot of research is required; watch the films and you get the tone fairly quickly. The only carryovers are that the main character has to have a vision of the upcoming disaster that allows him/her (and others around them) to momentarily avoid being killed, and that every death has to be as gruesome as possible (my editor said I could have “an orgy of blood”).

The one disadvantage was that, after my plot had been approved and I was about a month into the novel, the license owner, New Line Cinema, announced the plot for the next FD movie—and it was using the same disaster device as the one in my book! My plot had a roller coaster on the top of a Las Vegas casino coming off the tracks and falling off the building; Final Destination 3 also had a roller coaster jumping its tracks. (Great minds thinking alike, I guess.) That meant I had to go back and change my deathbringer, while still meeting the manuscript’s delivery date—it became a glass elevator running on the outside of a casino that falls off its track.

A great debate going on in the comics industry is the unrealistic portrayal of women and men. What’s your take on this? Is it getting better or worse?

You ask this of the guy who said his favorite kind of vampire was the half-naked Vampirella?

I don’t know about unrealistic portrayals of men in comics (all superheroes are unrealistic portrayals of men), but when people talk about the unrealistic portrayal of women, it’s usually in terms of objectification: female characters presented as male sexual fantasies. (See: Vampirella.)

When I was a teen in the 1970s, the same topic existed, although it wasn’t discussed as widely in those pre-pre-pre-Internet days. Unfortunately, the ’90s brought us the “Bad Girl Era,” where publishers practically tripped over one another in a rush to put out comics starring nearly naked heroines who didn’t fight crime as much as pose like supermodels on the page. It was an insane time, and a lot of those comics were absolute garbage.

Pan is actually my response to the objectification debate. With the concern these days about teens and body-consciousness issues, I thought having a female lead who wasn’t built like Wonder Woman might be a refreshing change of pace. Pan’s kind of short and tomboyish, although she can be a stunner when she glams up (she doesn’t always see it that way; then again, she’s got self-esteem problems). She’s an action heroine—I call her a “Goth adventuress”—who dresses in jeans and leather jackets.

Her mentor, monster hunter Sebastienne Mazarin, on the other hand, does look a little more like a superheroine, but that’s because she actually got her start in Heartstopper, a bad-girl book of my own that was published in the ’90s. After she got an extreme makeover, Annie looks much more respectable these days!

(To give you a quick mental image of Pan and Annie, here’s the “Hollywood high concept” line I often tell people at conventions: “Think Ellen Page and Salma Hayek in a Hellboy movie.”)

Are unrealistic portrayals of women in comics getting better or worse? I think they’re almost at the same levels they’ve always been—it’s just that the Internet has made it possible for the shouting on both sides of the debate to get louder and more vitriolic.

As long as comics remain a male-dominated, superhero-driven industry there’ll always be female characters in tight, revealing costumes—it’s what most male, superhero-comics artists live to draw! Therefore, it’s the responsibility of the writers to work with that limitation and make the characters interesting. If the story is good, the characterization is strong, and the artwork isn’t 100% cheesecake pinuppery, readers will accept a female character, even if she isn’t wearing pants. (See: Amanda Conner and Jimmy Palmiotti’s run on DC’s Power Girl series.)

FYI: Want to make male comic book artists groan in agony? Ask them to draw your heroine and then point out that she’s short, and kind of flat-chested. (See: Pandora Zwieback.) It’s like you’re punishing them!

What about the portrayal of teens in YA fiction today, such as Bella and Edward from Twilight?

Well, as I said, I don’t read a lot of teen lit, so I can only speak for my own work. (Recounting the grumbling I’ve heard from female friends about the Bella/Edward relationship wouldn’t count.)

Given the dark-fantasy setting, I try to keep Pan as realistic as possible. She’s never thought of her monster-seeing ability (she calls it “monstervision”) as anything other than a mental illness; her therapists over the years all agree. It’s only when she meets Annie, the monster hunter, that she discovers her power is a gift, not a curse.

Outside of her strange powers, Pan is fiercely loyal to her friends and her parents, vulnerable but strong-willed and funny, a talented artist, and a romantic with low-self-esteem issues (she gets a bit tongue-tied and awkward when she meets her new potential boyfriend). There are some dark personal moments in her past, which are hinted at in Blood Feud, and those will play out as the series progresses.

Can you give us a sneak peak of Pandora’s second adventure?

I wish I could, but Blood Feud ends on such a major cliffhanger that any details I give would ruin the first book for new readers. What I can say is that Blood Reign: The Saga of Pandora Zwieback, Book 2 will be on sale in June 2012, and that matters can only get potentially worse for Pan.

It’s not easy being a Goth adventuress!

2 thoughts on “Interview with Steven Roman, author of Blood Feud”

Comments are closed.